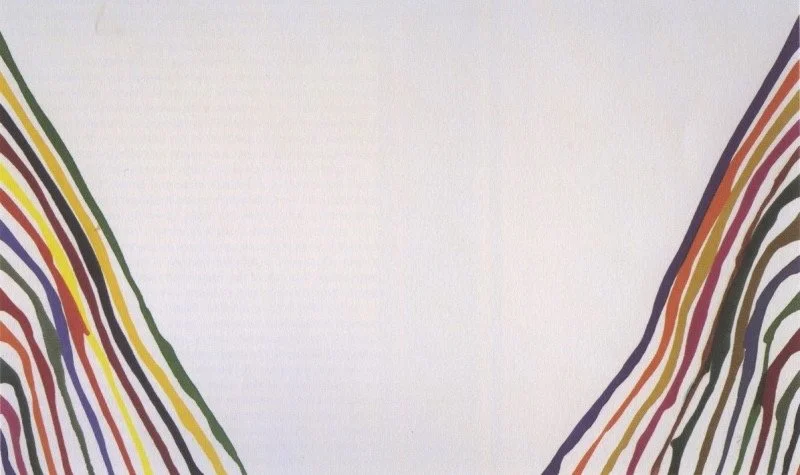

Morris Louis, Beta Mu, 1961

[Acrylic resin (Magna) on canvas]

Beta Mu hangs on a wall by itself. It’s massive: 102 x 170 inches. Thin lines of paint mixed with turpentine run down in diagonals and stain untreated canvas. The v-shaped center, the largest part, is naked. An inverted empty pyramid. It looks like two heaving lungs, I say to no one. A woman passing by turns and looks—at me, at the painting, at me. She walks away. What I mean is that it helps me to remember to breathe.

Roger Hilton: “Painting is a feeling. Just as much as a sentence describes, so a sequence of colors describes.”

“Breathing,” my therapist says. “Breathing is what helps your anxiety.” Inhaling through your nose activates the parasympathetic nervous system. It’s like’s an emergency brake. When you work on breathing through your nose in a calm manner, it tells your brain to call off any alarm that may be ringing. I try to remember this, but I often fail.

I’ve lived in Texas for over a decade, now. Moved here because my then wife accepted a tenure track job. I took a position at the same institution and everything went to shit. I’ve stopped lying when people ask how I like Texas. I hate it, I tell them. But the museums are world class. I consider myself lucky to have access to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. It has become a kind of sanctuary, a quiet place I can dip in and out of, that allows for reflection and examination. Not just on art.

There isn’t much to Beta Mu. Streaks of color start on the top corners of either side and wend their way like rivulets toward the bottom of the canvas. Louis is lumped in with painters categorized under “Color Field.” Color field was first used in the 1950s to describe the work of Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clyfford Still. But something changed in 1960, and color field started to shift into what Clement Greenberg called “post-painterly abstraction.” Louis, Helen Frankenthaler, they were like those artists before them: interrogating, examining color and space. But they had stripped something away. They eliminated the emotional, mystic content of earlier works, and the gestural applications of the 1950s movement.

Veil paintings, unfurled paintings. I have tried to understand the nomenclature. What is it that is being hidden or unrolled? I’m not interested in what the painting means. Neither am I all that interested in how the painting was made. Yes, I’m curious about technique, and the veil, and the un/furling, but, also, I don’t care. What I care about is how the work makes me feel.

Elsworth Kelly: “The form of my painting is the content.”

As I write, I experience that special tightness of anxiety. A constant questioning of what I’m doing—is it good enough, is it worth it, worth my time; maybe I’m just an imposter, pretending. I examine my depression, my mental health, and I wonder about Louis’. It feels nosy, impolite, in a way, to do this distant prying. A friend and one-time roommate, Chet LaMore, described Morris as “very reserved—non-communicative—to the degree which suggests ‘withdrawn’”. From 1943-1947, Louis lived with his parents and relied on financial support from his brother. The woman who would become his widow—then his next door neighbor—remembered seeing him sitting slumped in a porch chair, looking frustrated, and brooding. Louis was 30 years old, had moved back to Baltimore from New York, living again with his parents with no money, painting in the basement, and a lovestruck girl across the way.

At Greenberg’s suggestion, Louis sent nine paintings to the art dealer Pierre Matisse. In a letter, Louis wrote “Just finished rolling & wrapping ptgs to go to Matisse. It was the usual struggle with my normal doubts re the stuff continually rising & then concluding that they were, after all, ptgs I’d done & I’d have to let it stand at that this time.”

The usual struggle, my normal doubts… While viewing Beta Mu, what I really respond to, is the feeling of loneliness expressed in the cavernous white space. It’s a loneliness that feels like home. I recognize a similar loneliness in my own work—whether in essays, or photographs, or word paintings. Works that once finished find their ways into hiding spots. It’s a loneliness of someone trying to make sense of the world—where they belong, do they belong, how they’ll figure out a way to construct some kind of fragments that will help them make it through the day (just this one day and then we’ll worry about tomorrow). A loneliness that has become too comfortable.

Beta Mu falls into a category of “stain” paintings. Louis would pour a mixture of acrylic paint and turpentine onto an unsized, un-stretched canvas. He’d then lift and tilt the canvas to manipulate the paint—create abstract shapes and fields of colors. In the Veil Series (1954-1959), Louis used the staining method to create pools and floods of colors—an examination of pure color and space. Overlapping, superimposed waves of brilliant, curving color and shapes submerged in light. In the Unfurled Series of 1960, he continued this exploration using bright, thin streams of color poured at a diagonal across both sides of the canvas. Look at Beta Mu, with its soaked strips of green, orange, blue, yellow, brown, and pink carving out a valley of negative space. Linear in design. Bright in color. Beta Mu lacks in detail, and is open in composition. It seems designed to lead the eye beyond the borders and limits of the canvas.

What I like about Beta Mu, then, is that it doesn’t tell me how to feel—it doesn’t tell me anything—not what to think, not what to take away. It’s not didactic. It seems to be asking a question: “what if…?” And the result is the artist trying something, seeing what happens, and then trying again.